Is the appraisal good enough? And is it enough?

Every submission for scheduled jewelry has (or should have) an appraisal. But what makes an appraisal good—that is, useful to the insurer? And is an appraisal, on its own, enough?

Here’s a sample submission from one insurer’s files.

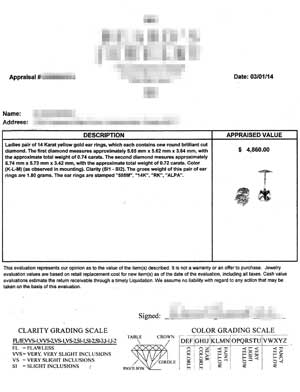

The appraisal looks good:

The jewelry description looks quite complete. A dense paragraph describes the metal and stone qualities, and the grading scales at the bottom help the client understand the quality grades given in the description.

The appraiser is a GG, meaning he’s a graduate gemologist of the GIA, a training credential that insurers can respect.

The appraisal is addressed to the customer, so the insurer knows it was prepared for the client now seeking insurance, and it is dated, so the insurer knows how recent the valuation is.

But . . . that’s not the whole story.

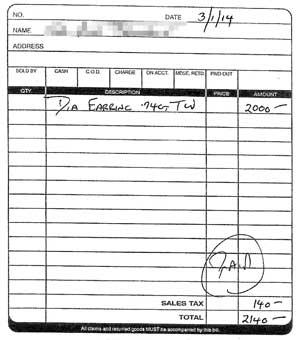

Fortunately, this insurer also asked for the sales receipt.

We can now see that, although the earrings sold for $2140, the appraisal valuation is $4860—more than twice the purchase price!

Grossly inflated jewelry valuations are common—more common that you might think.

In this case, the sales receipt tells us the appraisal was written by the seller of the jewelry (cropped off for privacy reasons, but take our word for it). Such appraisals merit extra attention from insurers because retailers are motivated to exaggerate the value of what they sell.

An extra irony: The boilerplate text above the appraiser’s signature says: “Jewelry evaluation values are based on retail replacement cost for new item(s) as of the date of the evaluation.” The seller knew the jewelry’s true replacement value but apparently didn’t mind the outright duplicity in more than doubling its appraised valuation.

Retailers convince customers they’re getting a bargain by supplying a document attesting to an inflated valuation. The customer is happy to have evidence that the jewelry is worth more than they paid. The inflated appraisal is often dismissed as “only for insurance,” with the implication that fooling the insurance company will somehow benefit the insured.

Of course it will not. In fact, it’s a disadvantage to the insured. If jewelry is insured for more than its value, the insured will be paying higher premiums than necessary. In the event of a claim, the settlement will be based on the insurer’s cost to replace, not on an inflated valuation.

What else is wrong?

The above scenario raises another question: If the appraisal’s valuation cannot be trusted, can the description be trusted?

In this description, the color grade spans 3 grades (K-L-M) and the clarity grade spans 2 grades (SI1-SI2). A diamond in the lowest position for both color and clarity would be 5 grades below a diamond in the highest position, meaning a significant difference in valuation.

Is the appraiser guessing? He notes that he graded the diamonds “as observed in mounting,” as though to excuse the vagueness of the grading. Being the seller of this jewelry, this appraiser should know the exact quality of each gem and not have to resort to approximate grades.

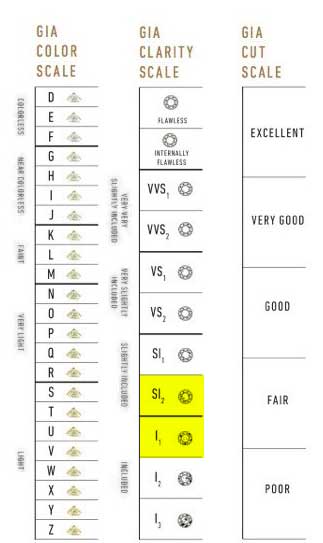

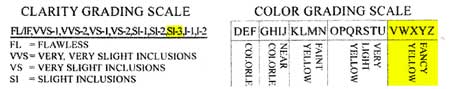

The Clarity and Color grading scales at bottom of the appraisal look official—but they are adulterated versions of the widely respected GIA grading scales. The appraisal’s Clarity scale adds in the grade SI-3. This is an invented grade, inserted to separate SI2 form I1. For accurate grading, a diamond whose clarity is below SI2 (Slightly Included) would be graded I1 (Included), meaning the gem has inclusions that are eye-visible, without use of a jeweler’s loupe.

Appraisal’s Grading scales

Appraisal’s Grading scales

Similarly, the appraisal’s Color scale mimics the GIA scale but is rewritten to make low-quality gems seem better than they are. The most egregious deception is describing V-Z grades as Fancy Yellow! These bottom-of-the-alphabet grades describe off-color, yellowish or brownish, diamonds that are far from having a desirable absence of color and are valued accordingly.

GIA Color grading scale for colorless diamonds

GIA Color grading scale for colorless diamonds

“Fancy” is a term gemologists use to describe diamonds with a strong color. Fancies are rare and generally quite expensive, and they are graded using a different system altogether.

And the appraisal does not mention Cut proportions—the most important of diamond’s 4 Cs.

What’s missing in this submission is an assessment on the gems’ qualities that is accurate, unbiased and based on a commonly accepted grading standard.

A report from a reputable gem grading lab such as GIA would give a detailed description of the gems, which would verify (or not!) the description on the seller’s appraisal. This is especially important for diamond jewelry, where an exaggerated color or clarity grade can make a big difference in valuation.

Not all grading labs are reputable! Some are notorious for inflating grades, some labs are subsidiaries of the retailer, and some are completely bogus labs. We recommend the following respected grading labs:

The higher the jewelry’s valuation, the more important it is to have a reliable lab report.

FOR AGENTS & UNDERWRITERS

A number of jewelry retailers supply their own appraisals and lab reports. Needless to say, such docs will necessarily support the claims of the retailer, and they also may omit or spin information that would negatively affect valuation. Request an appraisal from a gemologist appraiser who is independent of the seller.

The best appraisal includes the JISO 78/79 form, and is written by a qualified gemologist (GG, FGA+, or equivalent), preferably one who has additional insurance appraisal training. One course offering such additional training is the Certified Insurance Appraiser™ (CIA) course of the Jewelry Insurance Appraisal Institute.

At the very least, any appraisal should include all the information called for on the JISO form, which is the insurance industry’s standard for jewelry appraisals.

All diamonds of one carat or more should have a report from a respected independent grading lab. We recommend the following labs and suggest you use these links to verify reports you receive.

GIA Report Check

AGS Report Verification

GCAL Certificate Search

The higher the jewelry’s valuation, the more important it is to have a reliable lab report.

Always ask for the sales receipt, as it is a check against inflated valuations. A sales receipt tells you the purchase price, which is generally a good indication of market value.

FOR ADJUSTERS

Be aware that appraisals supplied by the seller are likely to have inflated valuations.

Base the settlement on descriptive information from the appraisal and lab report, not on the valuation.

Score the appraisal for completeness using JISO (formerly ACORD) 18, the Appraisal and Claim Evaluation form.

On a damage claim, ALWAYS have the jewelry examined in a gem lab that hasreasonable equipment for the job and is operated by a trained gemologist (GG, FGA+ or equivalent), preferably one who has additional insurance appraisal training, such as a Certified Insurance Appraiser™.

Comparing purchase price to the appraisal valuation is a useful way to avoid overpayment, as the price is usually a truer indication of market value than a possibly inflated valuation.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com