Padparadscha—a special term for a special stone

Whenever you encounter an unusual name or term on an appraisal, it's worth taking a second looks at the docs. And maybe doing a little research.

One insurer's experience:

The jewelry application arrived with an appraisal, a sales receipt, a GIA report, and a couple photos of the jewelry. So far, so good. The GIA report called the stone an orange sapphire, while the appraisal described the ring's stone as a padparadscha sapphire.

Was that important? The insurer consulted a Graduate Gemologist who'd been a retail jeweler for some 30 years, well experienced in dealing with colored gems. The gemologist could see that the valuation was too low for a true padparadscha—and too high for an orange sapphire. The jewelry owner had apparently been taken in by a good story from the seller.

Padparadscha's story

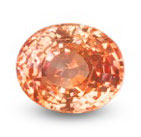

Padparadscha is a variety of sapphire highly valued for its striking display of color. The word itself means lotus color, and the gem has been poetically described as the marriage between a lotus flower and a sunset. The best padparadschas include blendings of yellow, pink, orange, and red.

All colored gems derive the greater part of their value from their color, and this is particularly true for the unique display in padparadschas.

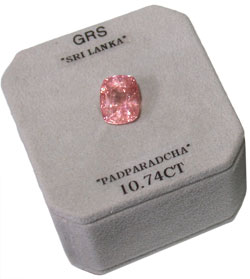

Padparadschas were originally found in Sri Lanka, and for some time only sapphires from this area could be considered true padparadschas. Later, deposits were also found in Madagascar and parts of East Africa, but the gem is still quite rare, and rarity adds to its value.

Photo courtesy of Lotus Gemology Natural Padparadscha |

In the gem trade there's always a danger of misrepresentation, especially with rare, high-value stones like padparadscha. In our earlier article, The Chanthaburi Connection, we reported on a scam in which low-quality corundum was heated to improve its color, and foreign materials were added to introduce different colors into the stone, producing padparadscha-looking stones. Suddenly a flood of supposedly rare gems entered the market. The cheap material, disguised by color treatments, was accepted as valuable padparadscha for some time before the fraud was discovered.

There is also the risk of a lab-grown stone being passed off as natural (mined). Lab-grown padparadschas are readily available on the Internet for under $100. The gem on the locket pictured here was described as lab-grown, but such disclosure is not always made.

In the case described above:

The insurer was suitably cautious, examining the documents and consulting an expert.

- The GIA report (view)

The Gemological Institute of America, like other labs, produces several kinds of lab reports, which include different data for different purposes. GIA states on its website that it will indicate on a sapphire identification report when a gem can be described as a padparadscha.

However, in this case what the insurer had was a GIA origin report. This origin report verified that the stone came from East Africa, an area known as a source for padparadscha (as well as for other, more common, sapphires!), but an origin report does not deal with whether or not the stone is a padparadscha. One can assume that whoever ordered the GIA report (probably the seller) chose carefully.

- The appraisal (view)

The only basis for regarding this as a padparadscha is that word of the appraisal. But this appraisal came from a lab unfamiliar to insurers and gemologists. There was no address or contact information for the lab on the appraisal or on the internet, and the client was not named on the appraisal. Most likely, this is a lab whose purpose is to supply feel-good appraisals for jewelry sellers to use as sales tools.

- Gemologist opinion

The GIA report stated that the gem had been heated, an accepted industry practice with sapphires, but it did not mention any other adulterations. Apparently this was not a faux padparadscha but simply an orange sapphire (as stated on the GIA report) being called padparadscha on the unreliable appraisal.

A Graduate Gemologist and Certified Insurance Appraiser, experienced in buying and selling colored gems for more than 30 years, advised insurer that the appraisal valuation was vastly inflated.

- Conclusion

Insuring this ring based on its appraisal valuation would present great moral hazard. At some point in the future the insured might take the ring to a jeweler for repair or cleaning and be told that the gem is, in fact, worth far less than she paid. And then she may decide to "lose" it for the insurance.

The insurer declined the risk.

FOR AGENTS & INSURERS

Beware of appraisals and certificates supplied by the seller. These are basically sales tools that often have exaggerated quality descriptions and inflated valuations.

High-value, purportedly rare, gems should always have their quality verified by a gemologist who is experienced in the buying and selling of that gem, is familiar with its pricing, and is aware of treatments and scams associated with that gem.

Recommend that your clients get an appraisal from a trained gemologist (GG, FGA+, or equivalent), preferably one who has additional insurance appraisal training. One course offering such additional training is the Certified Insurance Appraiser™ (CIA) course of the Jewelry Insurance Appraisal Institute.

Request a colored gem report from an internationally respected lab such are AGL (American Gemological Laboratories) or Gubelin Gem Lab. You can verify the contents of a report by contacting the labs.

If you encounter any terms on an appraisal or lab report that you don't understand, or brand names you're not familiar with, it might be worthwhile to consult a jewelry insurance professional working on your behalf. Some terms indicate quality, others can be names of lab-made gems (worth less than mined gems of the same quality), and still others can provide clues to inflated valuations.

FOR ADJUSTERS

While there are fewer claims on colored stones than on diamonds, colored stones usually have much higher markups and generally have inflated valuations.

Padparadschas are very rare in nature and are priced accordingly. In settling a claim on such a high-value sapphire, be sure the appraisal states that the gem is natural and untreated. Do not assume that if the appraisal doesn't mention treatments, the gem must be untreated; most likely, if treatment (or lack of it) is not mentioned, other information is incomplete as well.

For claims on damaged stones, always have high-priced jewelry inspected by an appraiser to determine whether the gems have been treated. Some treatments may break down, causing changes in the stone that are not damage for which the insurer is liable.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com