Chocolate Pearls — the Newest Flavor

Not since Cleopatra won a wager with Mark Antony by dropping her pearl earring into a goblet of wine, and then drinking down "the most expensive meal ever," has this jewel sounded so delicious. If Cleopatra's trick was the meal, chocolate pearls must be the dessert.

Chocolate is such a popular flavor it even sells jewelry. Making pearls a chocolaty brown is basically a treatment to produce another appealing version of an enduringly popular gem.

Chocolate is such a popular flavor it even sells jewelry. Making pearls a chocolaty brown is basically a treatment to produce another appealing version of an enduringly popular gem.

A Brief Look

at a Long History

Pearls have been highly regarded symbols of wealth since ancient Greece, Egypt, China, Imperial Rome, and Persia. Here in the West, Native Americans — and later, the colonists — harvested freshwater pearls from rivers and lakes, and saltwater pearls grew in beds along the coasts of Central and South America.

Only a very small percentage of oysters produce pearls. And only a fraction of those were ever harvested by humans, and only a handful of those harvested were of a desirable size, shape and color. This means that for centuries natural pearls were available to only the wealthy, royalty and the aristocracy.

Only a very small percentage of oysters produce pearls. And only a fraction of those were ever harvested by humans, and only a handful of those harvested were of a desirable size, shape and color. This means that for centuries natural pearls were available to only the wealthy, royalty and the aristocracy.

By the 19th century, the supplies of natural pearls began to dry up due to overharvesting and pollution caused by industry. Today, fine quality natural pearls exist primarily in private collections and are quite expensive.

For example, the "Baroda Pearls," a two-strand necklace of 68 impeccably matched graduated pearls, was recently offered at auction by Christie's. The necklace was considered the cornerstone of the Royal Treasury of the Maharaja of Baroda, one of the most prominent jewelry collectors of the 19th century. It shattered world auction records by selling for $7,096,000.

Enter the Cultured Pearl

Around the turn of the 20th century, Japanese researchers discovered techniques for cultivating pearls. Kokichi Mikimoto, who combined the best of the new techniques with creative and energetic marketing, is responsible for today's worldwide cultured pearl industry. Now instead of divers hunting, often in vain, for natural pearls, pearl farmers can cultivate crops of them.

Around the turn of the 20th century, Japanese researchers discovered techniques for cultivating pearls. Kokichi Mikimoto, who combined the best of the new techniques with creative and energetic marketing, is responsible for today's worldwide cultured pearl industry. Now instead of divers hunting, often in vain, for natural pearls, pearl farmers can cultivate crops of them.

Cultivated pearls grow the same way as natural pearls, but the process is initiated on purpose rather than by accident. A foreign substance enters (or is inserted into) the oyster. In response, the oyster surrounds the irritant with nacre, the same substance that lines the inside of the shell (where we call it "mother of pearl"). The nacre builds up in layers around the irritant to form the pearl.

Pearls tend to keep the shape of the initial irritant, or nucleus, so perfectly round pearls are extremely rare in nature. For cultured pearls, technicians can insert a round nucleus and thus produce more rounded pearls.

In nature, it's estimated that only one in 10,000 oysters produces a

gem-quality pearl. Pearl farmers, by contrast, harvest pearls by the thousands. In terms of both quality and availability, the farming of pearls has revolutionized the pearl industry.

Chocolate – and other Treat(ment)s

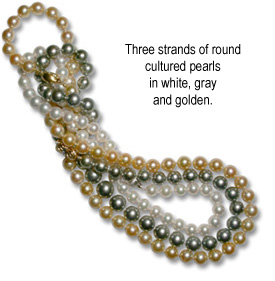

Chocolating the pearl is the latest fashion treatment. Pearls already come in a range of natural colors, including whites, yellows, golden, pinks, blues, grays, greens, and black, along with other "overtone" colors. Brown adds another color choice.

Chocolating the pearl is the latest fashion treatment. Pearls already come in a range of natural colors, including whites, yellows, golden, pinks, blues, grays, greens, and black, along with other "overtone" colors. Brown adds another color choice.

Chocolate pearls on the market come from several sources, which all have proprietary recipes for producing the color. One independent lab carefully examined several chocolate pearls, of various shades of brown, produced by Ballerina Pearl Co. The lab concluded that no coloring agents were added and that the color most likely resulted from bleaching black cultured pearls. Other sources may use other techniques to produce the brown color.

Pearls are routinely cleaned and polished, and are usually bleached, before sale.

Pearls are routinely cleaned and polished, and are usually bleached, before sale.

Some pearls are routinely "pinked" to given them a rose overtone. For decades silver nitrate has been used to darken the nacre, producing a rich black color. Other dyes may be added to produce colors other than black.

Irradiation is sometimes used to change the pearl's color by darkening the nucleus. Irradiated saltwater pearls appear gray or blue and may acquire an intense metallic sheen. All these treatments enhance the beauty of the pearl and do no harm.

On the other hand, coating a pearl to enhance its luster is a deceptive practice. This is equivalent to painting it with a coat of clear nail polish. The coating may eventually chip or peel, leaving a poor-quality, low-luster pearl.

How Pearls Are Valued

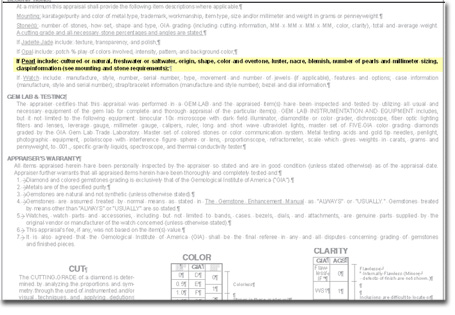

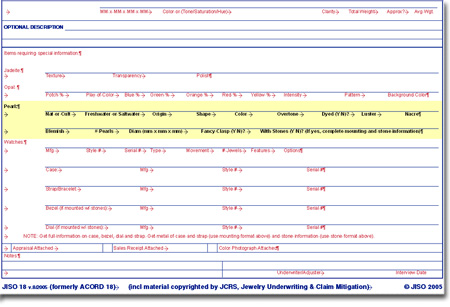

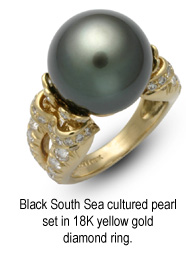

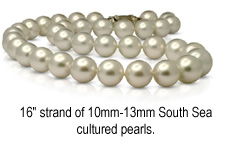

An appraisal for pearl jewelry should state whether the pearls are cultured or natural (the vast majority of pearls sold today are cultured), freshwater or saltwater, and should give origin, shape, color and overtone, luster, nacre, blemish, number of pearls on a strand, size in millimeters, and clasp and mounting information.

The appraiser looks at the luster and surface quality of the pearl. The surface may have cracks, bumps, pits or scratches. Sometimes a blemish is concealed by the setting. A pearl may exhibit signs of damage from bleaching or dying.

The appraiser looks at the luster and surface quality of the pearl. The surface may have cracks, bumps, pits or scratches. Sometimes a blemish is concealed by the setting. A pearl may exhibit signs of damage from bleaching or dying.

Thickness of the nacre is very important, since it helps determine how durable the pearl will be. Pearls are by nature vulnerable to damage. Their toughness rating is "poor to fair" (they can break or chip under impact) and their hardness rating is only 2.4 to 4.5 on the Mohs scale of 10 (they can be easily scratched, even through normal wear and tear).

Unfortunately, there is no universally accepted system for grading pearls as there is for diamonds. However, all the characteristics discussed above set the value of pearls, so they should be noted in detail on the appraisal.

It's especially important that the appraisal be prepared by a reliable jeweler, such as a Certified Insurance Appraiser™. The appraiser should be experienced in buying and selling pearls, have the training to provide accurate descriptions and the lab equipment for proper examination of the gem, and be aware of marketing trends and deceptive practices relating to pearls.

A Sample Scam

Beware of writing policies for "investment" gems that come in plastic bags with labels warning that the gems will lose value if the bag is opened. This is a red flag for fraud! A large carrier was recently taken for $120,000 over several strands of pearls insured in such a scam.

For a policy in that price range, an insurer should certainly require a second appraisal. If the gems cannot be examined for appraisal, they should not be insured.

FOR AGENTS & APPRAISERS

Be sure the appraisal comes from a jeweler who is a graduate gemologist (preferably a CIA™), who deals regularly with pearls, and who has examined the jewelry in a gem lab.

The appraisal should contain a detailed description, including all characteristics specific to pearls, as listed on the JISO 78/79 appraisal.

Check that the appraisal discusses treatments:

Treatments such as bleaching to improve color or dying to achieve rose, blue or gold overtones are "usual" treatments for pearls (as determined by the jewelry industry's Gemstone Information Manual.) These "usual" treatments are assumed to have been performed on pearls.

Treatments that should be specifically stated on the appraisal include the use of irradiation, heat or chemicals.

If pearls have not been subjected to treatments, the appraisal should state that the gems are untreated, since this could increase their value.

FOR ADJUSTERS

Examine damage claims carefully. Pearls are highly vulnerable to damage, even from normal wear and tear. They can also be harmed by a jeweler's torch and though improper cleaning by chemicals or boiling.

If you are working with a non-JISO appraisal, use JISO 18, Jewelry Appraisal & Claim Evaluation form. Refer to the section on pearls to organize information from the appraisal in hand and to be sure you have all necessary details for pricing a replacement.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com