Scam season is always NOW

As the holidays approach, we caution jewelry buyers and insurers to be even more vigilant than usual, since enthusiasm for gift shopping can cause consumers to relax their attention to detail and short-circuit their comparison shopping.

As the holidays approach, we caution jewelry buyers and insurers to be even more vigilant than usual, since enthusiasm for gift shopping can cause consumers to relax their attention to detail and short-circuit their comparison shopping.

Jewelry scams abound and, as we recount below, can occur all year long, in any local, and in all price ranges.

New York City's "Diamond District" is a stretch of 47th street in Manhattan where some 4,000 independent businesses are located, nearly all of them dealing in diamonds or jewelry. The area is widely regarded as a discount district, where prices are lower because of the competition, or a locale where retailers sell at wholesale prices, though that's not the case.

Nevertheless, the sheer concentration of jewelry retailers attracts clientele, and this year a spate of scam reports burst out of this destination diamond-shopping area.

Ex. 1. How did the diamond get pink?

In May, Donna Curry, who owns almost 300 subway franchises, bought a pink diamond ring from a Diamond District retailer for $270,000. Upon returning home to Las Vegas, she had the ring appraised and was told that the stone was artificially colored—and therefore worth considerably less than a naturally colored diamond would be.

She returned the ring and asked for her money back, saying that she had not been told the gem was color-treated. The store refused to refund her money, so she is suing them for over $1 million to cover punitive damages and lawyer fees. "It was a total fraud," said her lawyer. "She would have never bought the diamonds if she knew they were treated."

What we know:

Naturally colored pink diamonds are rare, and therefor expensive. But color enhancement, through HPHT or other methods, can turn lower quality white diamonds to pink, or to a number of other colors.

Naturally colored pink diamonds are rare, and therefor expensive. But color enhancement, through HPHT or other methods, can turn lower quality white diamonds to pink, or to a number of other colors.

Ultimately, what's at issue is lack of disclosure. Disclosing the treatment would have meant losing the sale, since this buyer did not want a treated stone.

A stone of this price should have been accompanied by a GIA report stating its qualities and stating that it had been color-enhanced. Was there no diamond report? Did the buyer not ask for some documentation of quality? At this point we don't know.

Ex. 2 Were the docs doctored?

Eva Ho, a tourist visiting from Hong Kong, bought a 12.77ct ruby-and-diamond ring for $350,000. The purchase came with an AGL report stating the ruby was from Burma and was not enhanced. Shortly afterwards she purchased from the same retailer a 73.8-carat ruby ring for $350,000. This ring also came with an AGL report. Later she bought from that retailer an $188,000 ruby bracelet said to be from Van Cleef & Arpels.

Ho said she later discovered that the rubies were "valueless composites," with heat treatment and lead glass clarity enhancement. The lawsuit she filed in Manhattan Supreme Court charged that the store had misrepresented both the quality of the stones and their origin, and that the AGL reports she was given with her purchase were fraudulent. This last charge was backed up by an affidavit from AGL's president.

Ho said she later discovered that the rubies were "valueless composites," with heat treatment and lead glass clarity enhancement. The lawsuit she filed in Manhattan Supreme Court charged that the store had misrepresented both the quality of the stones and their origin, and that the AGL reports she was given with her purchase were fraudulent. This last charge was backed up by an affidavit from AGL's president.

Altogether this customer spent $888,000. According to the suit, the total value of all the items is really less than $50,000.

What we know:

Composite rubies are poor quality, fractured stones that have been fracture-filled with lead glass—sometimes to the extent that the stone has more glass than gem material. A gemologist can easily distinguish a composite from solid ruby. Although they have been the subject of scams and scandals for some time – for example, the Macy's scandal – composites continue to be sold.

A Burmese ruby, on the other hand, is a rare thing. A Burmese ruby of high quality would be extremely valuable; it would certainly require a report from a reliable lab report, such as AGL.

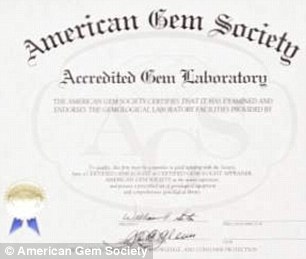

AGL, American Gemological Laboratories, is a highly regarded authority on grading colored gems. Consumers and insurers should feel confident with an AGL report in hand. But—AGL's president declared under oath that AGL did not write this report.

Unfortunately, fraudulent lab reports are an insidious problem. Bogus reports may come from disreputable or non-existent labs, and those are easier for an attentive agent or consumer to identify. The more troublesome ones are forged reports that seem to come from well-respected labs—such as AGL or GIA—and that may be what's at issue here.

And here's another kink in this case. This is how the retailer responded to an inquiry from JCK, a jewelry industry journal:

The entire story is a fabrication, apparently orchestrated to make an insurance claim. The stone was valued at no more than $350,000.00. The woman sent emails stating that she wanted it insured for $1.5 million. As it was quite suspicious, I refused to comply. Now the customer falsely claims the stone was fake. I was not then, and am not now, willing to be drawn into a fraud. The truth will come out in court.

So who is doing the scam? The consumer, aiming at an insurance claim? The retailer, using bogus lab reports to justify inflated values? Or, did the diamond dealer who sold the gems to the retailer make false claims and supply fraudulent docs? We wait to see if the truth "comes out in court."

Ex. 3 Undisclosed treatment & refund issues

In another incident, a couple bought a 5.38-carat diamond for $87,000. According to reports, the diamond turned out to be treated and the treatment was not disclosed.

What we know:

Non-disclosure is an all-too-common occurrence. It's a serious problem, because color and clarity treatments significantly lower the value of a gem.

Another common occurrence is what happens after discovering the problem, when a customer returns jewelry because it doesn't match the quality stated by the retailer.

For this couple, the store simply stalled, making promise after promise of a refund, and following up with delay after delay. In other cases the store has a "return" policy, but not for a cash refund. Instead, the store allows the customer to choose something else of equal value (or, more likely, equal inflated value). Or the retailer, as though doing the customer a favor, accepts the returned item in exchange only for store credit on an item of higher value.

The return policy may be mentioned in the fine print, but a buyer can easily overlook it in the thrill of the purchasing moment, or can interpret "return" to mean "return for a refund." In any case, when merchandise is represented as being of higher quality than it actually is, that's a scam. In our opinion, when a store refuses to give refunds on misrepresented merchandise, that's another scam.

Ex. 4 Stone Swapping

The stories above made the news because they involve big bucks and the famous Diamond District. But scams can happen anywhere.

Stone-swapping has recently been the subject of many complaints settling around the national chain Kay Jewelers.

This store sells an extended service plan: as long as the customer brings the jewelry in every six months for an inspection, certain services are free (ring sizing, prong replacement, chain soldering, clasp replacement, and the like). According to reports on internet sites, a number of customers who took their rings to Kay for inspection or repair have gotten their jewelry back with different stones.

Moissanite

Picture courtesy of Charles & Colvard, Ltd.

One customer reported that her ring just didn't look right. She had it examined by two other jewelers, both of whom determined that her ring was not diamond set in white gold, as described on her Certificate of Authenticity from Kay, but moissanite set in platinum. All moissanite available today is lab-made stone, similar in appearance to diamond but having about one-tenth the value of diamond.

When she returned the ring to Kay, they tested it and insisted that it tested as diamond. Kay also had the stone tested at Zales (which is owned by the same parent company as Kay), and that test also came out as diamond. The customer was told that the store's loss protection team would look into the issue.

BuzzFeed, an internet site, found several dissatisfied customers complaining on social media of similar incidents. And after the woman above posted her story on Facebook, she said she was contacted by "hundreds" of people with comparable stories.

The women who claim their diamonds were swapped found the experience heartbreaking. One woman reported that the diamond in her engagement ring had been replaced with an obviously lower-quality diamond, as verified by an independent appraisal. After protesting to Kay for some time and getting nowhere, she finally just gave up—and no longer wears the ring. "It's not the diamond my husband got for me – it has no sentimental value. I don't want to have an engagement ring that brings bad memories."

What we know:

Swapping out a gem for a lower-quality stone is easily accomplished when jewelry is left for cleaning or repair. Reports of this scam make the news only from time to time, but it is probably an ongoing problem. We can't know for sure how often it happens because jewelry owners may not see the difference. Or, if they confront the store and the store stonewalls, they may feel they have little recourse.

The people who bought six-figure jewelry in the Diamond District can afford the time and expense of a lawsuit. For those who paid under $5,000, like the Kay customers above, a lawsuit may not be a viable option for recovering their losses.

Gemological Science International (GSI), a lab used by Kay for its "Certificates of Authenticity," grades diamonds in mass numbers for some of the large chain stores. This lab does not have a good reputation among gemologists and we do not recommend relying upon its reports or certificates. Since Kay is buying a large number of certs, possibly in bulk, it is possible that the certificate given to the customer did not match the customer's jewelry to begin with.

Note: Gems shown on this page are for illustration only; they are not the gems involved in the alleged frauds discussed.

FOR AGENTS & UNDERWRITERS

DISCLOSURE!

- Whether through ignorance, carelessness or deliberate fraud, information about treatments is often lacking on appraisals. All information about the jewelry's quality affects its value.

- Non-disclosure happens at every price point.

- We cannot emphasize strongly enough the need to check appraisals and lab reports for information about gem treatments. Look for these terms: treated, enhanced, composite. A color-treated or clarity-treated gem has a lower value than an untreated gem of similar appearance.

- One consumer noticed the initials C.E. off in the corner of her lab report. She found out—too late—it stood for Clarity Enhancement. Note that a report from a reliable lab would not hide or camouflage such information.

- If there are no treatments, the appraisal should explicitly state that the stone is untreated. This lets you know the appraiser has made a determination and not simply overlooked or avoided the issue of treatments.

- Also look for terms that denote lab-made stones, such as: grown, lab-grown, synthesized, man-made. Lab-made diamonds are real diamond, but they have a substantially lower valuation that mined diamonds.

High value or important jewelry often has a lab report, whether or not that is indicated on the appraisal, so the underwriter should request it. Depending on the insurance company's guidelines, you may want to make a lab report mandatory.

We recommend reports from these widely respected labs:

GIA

AGL

Gübelin

AGS Report Verifcation

GCAL Certificate Search

Beware of pre-done appraisals and certificates supplied by the seller. These are basically sales tools that often have exaggerated quality descriptions and inflated valuations.

The best appraisal includes the JISO 78/79 appraisal form, and is written by a qualified gemologist (GG, FGA+, or equivalent) who has additional insurance appraisal training. One course offering such additional training is the Certified Insurance Appraiser™ (CIA) course of the Jewelry Insurance Appraisal Institute.

FOR ADJUSTERS

Comb the appraisal and lab report for terms denoting treatments, as described above.

Always have damaged jewelry inspected by a trained gemologist—GG, FGA+, or equivalent, and preferably a CIA—to verify the quality of the gem matches what is represented on the appraisal and lab report.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com

Naturally colored pink diamonds are rare, and therefor expensive. But color enhancement, through HPHT or other methods, can turn lower quality white diamonds to pink, or to a number of other colors.

Naturally colored pink diamonds are rare, and therefor expensive. But color enhancement, through HPHT or other methods, can turn lower quality white diamonds to pink, or to a number of other colors.Eva Ho, a tourist visiting from Hong Kong, bought a 12.77ct ruby-and-diamond ring for $350,000. The purchase came with an AGL report stating the ruby was from Burma and was not enhanced. Shortly afterwards she purchased from the same retailer a 73.8-carat ruby ring for $350,000. This ring also came with an AGL report. Later she bought from that retailer an $188,000 ruby bracelet said to be from Van Cleef & Arpels.

Ho said she later discovered that the rubies were "valueless composites," with heat treatment and lead glass clarity enhancement. The lawsuit she filed in Manhattan Supreme Court charged that the store had misrepresented both the quality of the stones and their origin, and that the AGL reports she was given with her purchase were fraudulent. This last charge was backed up by an affidavit from AGL's president.

Ho said she later discovered that the rubies were "valueless composites," with heat treatment and lead glass clarity enhancement. The lawsuit she filed in Manhattan Supreme Court charged that the store had misrepresented both the quality of the stones and their origin, and that the AGL reports she was given with her purchase were fraudulent. This last charge was backed up by an affidavit from AGL's president.

Altogether this customer spent $888,000. According to the suit, the total value of all the items is really less than $50,000.

What we know:

Composite rubies are poor quality, fractured stones that have been fracture-filled with lead glass—sometimes to the extent that the stone has more glass than gem material. A gemologist can easily distinguish a composite from solid ruby. Although they have been the subject of scams and scandals for some time – for example, the Macy's scandal – composites continue to be sold.

A Burmese ruby, on the other hand, is a rare thing. A Burmese ruby of high quality would be extremely valuable; it would certainly require a report from a reliable lab report, such as AGL.

AGL, American Gemological Laboratories, is a highly regarded authority on grading colored gems. Consumers and insurers should feel confident with an AGL report in hand. But—AGL's president declared under oath that AGL did not write this report.

Unfortunately, fraudulent lab reports are an insidious problem. Bogus reports may come from disreputable or non-existent labs, and those are easier for an attentive agent or consumer to identify. The more troublesome ones are forged reports that seem to come from well-respected labs—such as AGL or GIA—and that may be what's at issue here.

And here's another kink in this case. This is how the retailer responded to an inquiry from JCK, a jewelry industry journal:

The entire story is a fabrication, apparently orchestrated to make an insurance claim. The stone was valued at no more than $350,000.00. The woman sent emails stating that she wanted it insured for $1.5 million. As it was quite suspicious, I refused to comply. Now the customer falsely claims the stone was fake. I was not then, and am not now, willing to be drawn into a fraud. The truth will come out in court.

So who is doing the scam? The consumer, aiming at an insurance claim? The retailer, using bogus lab reports to justify inflated values? Or, did the diamond dealer who sold the gems to the retailer make false claims and supply fraudulent docs? We wait to see if the truth "comes out in court."

Ex. 3 Undisclosed treatment & refund issues

In another incident, a couple bought a 5.38-carat diamond for $87,000. According to reports, the diamond turned out to be treated and the treatment was not disclosed.

What we know:

Non-disclosure is an all-too-common occurrence. It's a serious problem, because color and clarity treatments significantly lower the value of a gem.

Another common occurrence is what happens after discovering the problem, when a customer returns jewelry because it doesn't match the quality stated by the retailer.

For this couple, the store simply stalled, making promise after promise of a refund, and following up with delay after delay. In other cases the store has a "return" policy, but not for a cash refund. Instead, the store allows the customer to choose something else of equal value (or, more likely, equal inflated value). Or the retailer, as though doing the customer a favor, accepts the returned item in exchange only for store credit on an item of higher value.

The return policy may be mentioned in the fine print, but a buyer can easily overlook it in the thrill of the purchasing moment, or can interpret "return" to mean "return for a refund." In any case, when merchandise is represented as being of higher quality than it actually is, that's a scam. In our opinion, when a store refuses to give refunds on misrepresented merchandise, that's another scam.

Ex. 4 Stone Swapping

The stories above made the news because they involve big bucks and the famous Diamond District. But scams can happen anywhere.

Stone-swapping has recently been the subject of many complaints settling around the national chain Kay Jewelers.

This store sells an extended service plan: as long as the customer brings the jewelry in every six months for an inspection, certain services are free (ring sizing, prong replacement, chain soldering, clasp replacement, and the like). According to reports on internet sites, a number of customers who took their rings to Kay for inspection or repair have gotten their jewelry back with different stones.

Moissanite

Picture courtesy of Charles & Colvard, Ltd.

One customer reported that her ring just didn't look right. She had it examined by two other jewelers, both of whom determined that her ring was not diamond set in white gold, as described on her Certificate of Authenticity from Kay, but moissanite set in platinum. All moissanite available today is lab-made stone, similar in appearance to diamond but having about one-tenth the value of diamond.

When she returned the ring to Kay, they tested it and insisted that it tested as diamond. Kay also had the stone tested at Zales (which is owned by the same parent company as Kay), and that test also came out as diamond. The customer was told that the store's loss protection team would look into the issue.

BuzzFeed, an internet site, found several dissatisfied customers complaining on social media of similar incidents. And after the woman above posted her story on Facebook, she said she was contacted by "hundreds" of people with comparable stories.

The women who claim their diamonds were swapped found the experience heartbreaking. One woman reported that the diamond in her engagement ring had been replaced with an obviously lower-quality diamond, as verified by an independent appraisal. After protesting to Kay for some time and getting nowhere, she finally just gave up—and no longer wears the ring. "It's not the diamond my husband got for me – it has no sentimental value. I don't want to have an engagement ring that brings bad memories."

What we know:

Swapping out a gem for a lower-quality stone is easily accomplished when jewelry is left for cleaning or repair. Reports of this scam make the news only from time to time, but it is probably an ongoing problem. We can't know for sure how often it happens because jewelry owners may not see the difference. Or, if they confront the store and the store stonewalls, they may feel they have little recourse.

The people who bought six-figure jewelry in the Diamond District can afford the time and expense of a lawsuit. For those who paid under $5,000, like the Kay customers above, a lawsuit may not be a viable option for recovering their losses.

Gemological Science International (GSI), a lab used by Kay for its "Certificates of Authenticity," grades diamonds in mass numbers for some of the large chain stores. This lab does not have a good reputation among gemologists and we do not recommend relying upon its reports or certificates. Since Kay is buying a large number of certs, possibly in bulk, it is possible that the certificate given to the customer did not match the customer's jewelry to begin with.

Note: Gems shown on this page are for illustration only; they are not the gems involved in the alleged frauds discussed.

FOR AGENTS & UNDERWRITERS

DISCLOSURE!

- Whether through ignorance, carelessness or deliberate fraud, information about treatments is often lacking on appraisals. All information about the jewelry's quality affects its value.

- Non-disclosure happens at every price point.

- We cannot emphasize strongly enough the need to check appraisals and lab reports for information about gem treatments. Look for these terms: treated, enhanced, composite. A color-treated or clarity-treated gem has a lower value than an untreated gem of similar appearance.

- One consumer noticed the initials C.E. off in the corner of her lab report. She found out—too late—it stood for Clarity Enhancement. Note that a report from a reliable lab would not hide or camouflage such information.

- If there are no treatments, the appraisal should explicitly state that the stone is untreated. This lets you know the appraiser has made a determination and not simply overlooked or avoided the issue of treatments.

- Also look for terms that denote lab-made stones, such as: grown, lab-grown, synthesized, man-made. Lab-made diamonds are real diamond, but they have a substantially lower valuation that mined diamonds.

High value or important jewelry often has a lab report, whether or not that is indicated on the appraisal, so the underwriter should request it. Depending on the insurance company's guidelines, you may want to make a lab report mandatory.

We recommend reports from these widely respected labs:

GIA

AGL

Gübelin

AGS Report Verifcation

GCAL Certificate Search

Beware of pre-done appraisals and certificates supplied by the seller. These are basically sales tools that often have exaggerated quality descriptions and inflated valuations.

The best appraisal includes the JISO 78/79 appraisal form, and is written by a qualified gemologist (GG, FGA+, or equivalent) who has additional insurance appraisal training. One course offering such additional training is the Certified Insurance Appraiser™ (CIA) course of the Jewelry Insurance Appraisal Institute.

FOR ADJUSTERS

Comb the appraisal and lab report for terms denoting treatments, as described above.

Always have damaged jewelry inspected by a trained gemologist—GG, FGA+, or equivalent, and preferably a CIA—to verify the quality of the gem matches what is represented on the appraisal and lab report.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com

The stories above made the news because they involve big bucks and the famous Diamond District. But scams can happen anywhere.

Stone-swapping has recently been the subject of many complaints settling around the national chain Kay Jewelers.

This store sells an extended service plan: as long as the customer brings the jewelry in every six months for an inspection, certain services are free (ring sizing, prong replacement, chain soldering, clasp replacement, and the like). According to reports on internet sites, a number of customers who took their rings to Kay for inspection or repair have gotten their jewelry back with different stones.

Moissanite Picture courtesy of Charles & Colvard, Ltd. |

One customer reported that her ring just didn't look right. She had it examined by two other jewelers, both of whom determined that her ring was not diamond set in white gold, as described on her Certificate of Authenticity from Kay, but moissanite set in platinum. All moissanite available today is lab-made stone, similar in appearance to diamond but having about one-tenth the value of diamond.

When she returned the ring to Kay, they tested it and insisted that it tested as diamond. Kay also had the stone tested at Zales (which is owned by the same parent company as Kay), and that test also came out as diamond. The customer was told that the store's loss protection team would look into the issue.

BuzzFeed, an internet site, found several dissatisfied customers complaining on social media of similar incidents. And after the woman above posted her story on Facebook, she said she was contacted by "hundreds" of people with comparable stories.

The women who claim their diamonds were swapped found the experience heartbreaking. One woman reported that the diamond in her engagement ring had been replaced with an obviously lower-quality diamond, as verified by an independent appraisal. After protesting to Kay for some time and getting nowhere, she finally just gave up—and no longer wears the ring. "It's not the diamond my husband got for me – it has no sentimental value. I don't want to have an engagement ring that brings bad memories."

What we know:

Swapping out a gem for a lower-quality stone is easily accomplished when jewelry is left for cleaning or repair. Reports of this scam make the news only from time to time, but it is probably an ongoing problem. We can't know for sure how often it happens because jewelry owners may not see the difference. Or, if they confront the store and the store stonewalls, they may feel they have little recourse.

The people who bought six-figure jewelry in the Diamond District can afford the time and expense of a lawsuit. For those who paid under $5,000, like the Kay customers above, a lawsuit may not be a viable option for recovering their losses.

Gemological Science International (GSI), a lab used by Kay for its "Certificates of Authenticity," grades diamonds in mass numbers for some of the large chain stores. This lab does not have a good reputation among gemologists and we do not recommend relying upon its reports or certificates. Since Kay is buying a large number of certs, possibly in bulk, it is possible that the certificate given to the customer did not match the customer's jewelry to begin with.

Note: Gems shown on this page are for illustration only; they are not the gems involved in the alleged frauds discussed.

FOR AGENTS & UNDERWRITERS

DISCLOSURE!

- Whether through ignorance, carelessness or deliberate fraud, information about treatments is often lacking on appraisals. All information about the jewelry's quality affects its value.

- Non-disclosure happens at every price point.

- We cannot emphasize strongly enough the need to check appraisals and lab reports for information about gem treatments. Look for these terms: treated, enhanced, composite. A color-treated or clarity-treated gem has a lower value than an untreated gem of similar appearance.

- One consumer noticed the initials C.E. off in the corner of her lab report. She found out—too late—it stood for Clarity Enhancement. Note that a report from a reliable lab would not hide or camouflage such information.

- If there are no treatments, the appraisal should explicitly state that the stone is untreated. This lets you know the appraiser has made a determination and not simply overlooked or avoided the issue of treatments.

- Also look for terms that denote lab-made stones, such as: grown, lab-grown, synthesized, man-made. Lab-made diamonds are real diamond, but they have a substantially lower valuation that mined diamonds.

High value or important jewelry often has a lab report, whether or not that is indicated on the appraisal, so the underwriter should request it. Depending on the insurance company's guidelines, you may want to make a lab report mandatory.

We recommend reports from these widely respected labs:

GIA

AGL

Gübelin

AGS Report Verifcation

GCAL Certificate Search

Beware of pre-done appraisals and certificates supplied by the seller. These are basically sales tools that often have exaggerated quality descriptions and inflated valuations.

The best appraisal includes the JISO 78/79 appraisal form, and is written by a qualified gemologist (GG, FGA+, or equivalent) who has additional insurance appraisal training. One course offering such additional training is the Certified Insurance Appraiser™ (CIA) course of the Jewelry Insurance Appraisal Institute.

FOR ADJUSTERS

Comb the appraisal and lab report for terms denoting treatments, as described above.

Always have damaged jewelry inspected by a trained gemologist—GG, FGA+, or equivalent, and preferably a CIA—to verify the quality of the gem matches what is represented on the appraisal and lab report.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com