High-end jewelry & its docs

High-end jewelry & its docs

Suppose you get a submission for coverage on a pricey piece of jewelry. It comes with the docs — appraisal, lab report, sales receipt, photos, and a statement about warrantees from the high-end, famous-name retailer. An easy risk to accept? Time to relax?

Don’t be so sure. It’s always important to examine the appraisal and other documents, even when (or especially when) the jewelry is from a well-known high-end seller.

Here’s a look at one submission.

Appraisal:

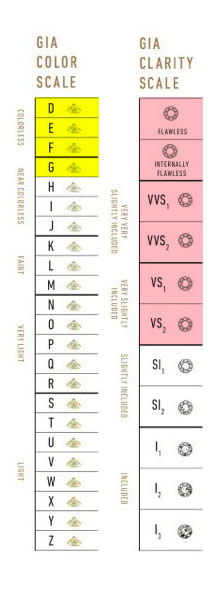

One platinum and diamond ring, prong-set at center with one round brilliant cut diamond weighing 5.63 carats, I color, VS1 clarity, pavé set on the prongs and shank with round brilliant cut diamonds weighing approximately .22 carat total weight, D-G color range, Internally Flawless-VS2 clarity range.

Estimated retail replacement value: $300,000+.

What the underwriter noticed:

The weight of the platinum mounting was not given. Was the setting light weight or substantial? The insurer cannot assume.

The weight of the platinum mounting was not given. Was the setting light weight or substantial? The insurer cannot assume.

- The accent diamonds had a 4-grade color range (D-G) and a 6-grade clarity range (IF-VS2). Although these accent diamonds are small, for jewelry at this price point the stones should be more closely matched as to color and clarity.

- The appraisal and diamond certificate came from the retailer, so there was no description of the gem or jewelry from a source independent of the seller.

- The replacement valuation on the appraisal was the same as the selling prince—which is not surprising since the appraisal came from the retailer. Because famous brands often have exorbitant markups, the underwriter decided to check whether this valuation was reasonable.

The center diamond is the primary determinant of the ring’s value, so the task was to find out how much diamonds like this typically are selling for. Blue Nile is a good place to check the current market value of diamonds, as that retail site allows you to “build your own ring” by specifying the qualities of the diamond. Using information from the appraisal for cut, color, clarity and carat weight of this ring’s center diamond, the underwriter located a diamond of similar quality for $121,338.

- A reasonable price for this ring, including the center diamond, the tiny accent diamonds, the platinum setting, and a profit for the seller, was judged to be $150,000-$175,000 — about half the price paid by the customer, and half the appraisal’s valuation.

What accounts for that extra $125,000-$150,000? Apparently, it’s the seller’s name.

So the insurer considered:

- Is it appropriate to insure a ring for more than $300,000 if its realistic market value is half that price?

- If the ring is insured for its $300,000+ price, but half the valuation is due to the retailer’s name, is the retailer’s name part of what’s being insured?

- Although this ring may bear the name of a high-end retailer, neither the diamond nor the ring design is unique. The piece is, in fact, rather generic, as the auction/secondary market shows. Is the insurer required to use the famous brand for a replacement, even though the piece could be duplicated at a far lower price?

A deeper look at what’s involved:

The submission also included a boilerplate letter from the jeweler to the purchaser with some misleading contents:

The seller “guarantees the grade of your diamond – for life. Other independent lab reports do not contain such guarantees.” [Emphasis added.]

Well, other labs don’t give such guarantees because they are meaningless. A diamond’s grades, its 4 Cs, do not change — as De Beers’ slogan “A diamond is forever” reminds us! A lab, an appraiser, a retailer, should stand behind the accuracy of their grading, but the longevity of the grades is a given.

“Not all insurance covers the replacement of lost or stolen items with identically branded merchandise. Many policies state ‘replacement with like kind’ which may mean that your [brand name] jewelry will not be replaced with [brand name] merchandise. We suggest that you review your policy carefully.”

This passage encourages an adversarial relationship with the insurer. It sets the stage for the insured not trusting their insurer in the event of a loss.

Our first response is that “replacement with like kind” is layman’s language, not legal language, and it probably doesn’t appear on the jewelry policy.

The retailer’s warning suggests to the purchaser that any replacement must be “identically branded.” It implies that the jewelry’s brand determines its value. In truth, jewelry’s value is determined by it component parts.

All jewelry retailers, high-end or not, famous name or not, would like insurance replacements for their merchandise to come from them. But this is not necessarily the best business practice for insurers. To keep costs down, it is in the public’s interest for the insurer to settle claims at a fair but not inflated value.

The price difference between a ring from a prestige retailer versus the same jewelry without the famous name turns out to be the price of the shopping experience. Once the purchase is made, the value attached to the shopping experience is lost. The experience is not measurable, and it’s not insurable.

What the jewelry buyer should be wary of is insurers who take advantage of the insured by charging premiums based on inflated valuations, when a loss is settled at the insurer’s cost of replacement at time of loss.

The letter closes with an invitation to call the retailer if further assistance is needed.

After the warning about insurance policies, it’s likely that in the event of a loss, the insured’s first response might be to call the jewelry seller for assistance. Since the sales rep would be likely to advise the customer to insist on a replacement from the same high-end store, is that salesperson giving insurance advice?

FOR AGENTS & UNDERWRITERS

Make no assumptions about the value of a brand. Customers usually assume that if they’re buying a prestige brand they are getting good quality. Presumably, a buyer likes the jewelry and is willing to pay the price. For the insurer, there are other considerations.

A number of retailers have started supplying their own appraisals and lab reports. Needless to say, such docs will necessarily mimic the claims of the retailer, and they also may omit or spin information that would negatively affect valuation. Request an appraisal from an appraiser who is independent of the seller.

The best appraisal includes the JISO 78/79 appraisal form and is written by a qualified gemologist (GG, FGA+, or equivalent), preferably one who has additional insurance appraisal training. One course offering such additional training is the Certified Insurance Appraiser™ (CIA) course of the Jewelry Insurance Appraisal Institute.

All diamonds of one carat or more should have a report from a nationally respected independent lab. Labs can afford the instruments needed to distinguish mined diamonds from their less-valuable counterparts that are lab-grown, and they have gemologists with the expertise to recognize gem treatments. We recommend the following labs and suggest that you use these links to verify reports you receive.

GIA Report Check

AGS Report Verification

GCAL Certificate

FOR ADJUSTERS

Pay attention to brand names, but don’t take them at face value as everything can be counterfeited these days.

Base the settlement on descriptive information from the appraisal and lab report, not on the valuation.

On a damage claim, ALWAYS have the jewelry examined in a gem lab that has reasonable equipment for the job and is operated by a trained gemologist (GG, FGA+ or equivalent), preferably one who has additional insurance appraisal training, such as a Certified Insurance Appraiser™.

©2000-2025, JCRS Inland Marine Solutions, Inc. All Rights Reserved. www.jcrs.com